With ARPA funds depleted, Madison area food pantries look for strategies to keep the shelves stocked. – Isthmus

“We have come to use the phrase ‘rent eats first,’” says Meghan Sohns of WayForward Resources in Middleton. “People will do whatever they have to in order to stay in their homes.” And that often means that once the rent is paid, there’s little left for food, sending families to food pantries.

A pileup of causes are increasing demand. Additional pandemic-era food assistance to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) ended in March 2023. Funds from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, distributed by Dane County and used by Second Harvest Foodbank of Southern Wisconsin to buy such staples as milk, eggs, produce and protein, will run out at the end of this year, leaving the foodbank with a $5.5 million gap in funding. Food costs themselves have risen, as have housing costs. And there are simply more people in Dane County, the fastest growing county in Wisconsin.

In June, WayForward was facing shortages in its food pantry.

“I was really concerned about the increase in demand and the empty shelves and constraints on our budget,” says Sohns, program director at WayForward (formerly Middleton Outreach Ministry), a nonprofit that focuses on food and housing security. The group came up with a novel approach to raise awareness: sending out a joint letter to the public from 36 Madison-area food pantries and food banks.

“We thought, what if, as a collective, we went to the community as an education opportunity but also a call to action — with different ways to take action?” Sohns remembers.

Sohns calls the letter “a great first step.” WayForward’s June campaign for $150,000 was met in donations. But just as importantly, the letter started a conversation “about advocacy and what it looks like in the community,” says Sohns. “What would it take to have a collective workgroup on advocacy at the local government level? I think we’re just getting started.”

In addition to its food pantry, WayForward offers a food delivery option to those who qualify, a mobile food pantry that visits low income neighborhoods, and a garden where guests can pick their own fresh produce.

“The surge of donations over the summer helped us and we are grateful, but that will dwindle,” Sohns says. Pantry visits to WayForward nearly doubled from last year, from 61,533 in the 2023 fiscal year to 115,142 in the 2024 fiscal year. Sohns expects to surpass that in 2025.

“We need long-term solutions,” says Sohns. “We need to think about the long game.”

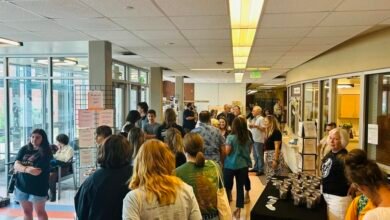

In September 2022, Badger Prairie Needs Network returned to indoor “choice” shopping at its food pantry, after 900 days of curbside pickups of pre-bagged groceries during the pandemic. Like other pantries, it shifted to the curbside model to safeguard the health of shoppers and volunteers, in the days when people were being urged to wash their groceries.

But indoor shopping works better, says Tracy Burton, pantry director at Badger Prairie. It gives shoppers agency. And there’s less waste. In the bagged days, the average family size cart contained 140 pounds of food; now the average family cart is 90 pounds of food, which tells the pantry that many of the preselected groceries were not being used — they even noticed some donated back to the pantry.

“People need choice,” says Burton, noting that 65% of Badger Prairie’s users are Hispanic and choose culturally familiar food. Badger Prairie stocks such items as masa harina and masa arepa, plantains, and cilantro, “things that you wouldn’t normally find at a food pantry, so that the people who come to us can cook the meals their families will eat — and it keeps them connected to their cultural identity,” says Burton.

Going back to choice shopping reduced BPNNs costs. However, that savings is offset by increasing demand, says Burton.

Badger Prairie is funded by grants and donations, and gets food from a variety of sources, including Second Harvest, leftovers from Epic Systems cafeterias, and food drives. It also serves a free community meal the first and third Saturdays of each month, to fill in the gap on a day when school lunches and senior sites don’t serve.

Food drives raise community awareness, says Burton, and they bring in foods the pantry would likely not get from Second Harvest. However she finds focused food drives are the most successful, such as recent Verona Area High School drives in partnership with Miller and Sons Supermarket. Badger Prairie tells the organizers what items are most needed, the store puts those on sale, high school students collect the foods at the store, and deliver and stock them at the pantry. “We get exactly what we need, the right food at the right time, perfect solutions.”

Burton warns the looming expiration of the federal ARPA funds (distributed by Dane County to Second Harvest) is “a big rolling thing that’s going to happen,” causing smaller pantries to offer only canned donations, which will send more people to the larger pantries — that will already be needing to buy more of the staples they are currently receiving from Second Harvest.

Pantries understand that families may end up going to more than one pantry. “Anyone who comes to a food pantry needs food — they’re hungry and need to feed their family,” says Burton. “As pleasant as we try to make it, it’s not a great experience.”

The River Food Pantry continues to distribute groceries curbside. The River asks that cars not line up until 15 minutes before the pantry opens to decrease impeding traffic on Packers Avenue, but at the opening time of 9:30 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, 40-some cars were in line, trailing out into the road.

“We don’t run out of food,” says Helen Osborn-Senatus, director of operations at The River. “We look at our inventory and know we will get through the day.” But cars arriving as early as possible speaks to the “heightened stress people feel, facing food insecurity.”

The River casts its net “as broadly as possible” to get food, says Osborn-Senatus, gleaning excess from grocery stores and Kwik Trips. They also purchase food with donations, which allows them to buy wholesale and in bulk.

Curbside pickup and delivery to homebound individuals are key services. They’re joined by the Munch van, which delivers mobile meals to low-income neighborhoods; a once-a-month option to order specific groceries online; and an after-hours emergency food locker system located at the front of the building. The lockers provide a stopgap supply of non-perishable food and are accessed via a QR code.

The River just broke ground on a new building across the street from its current location. It will include more space for the pantry, dedicated drive-through, commercial kitchen, space for congregate meals, and offices for agencies that will help people address the root causes of food insecurity.

“We would not survive without community support,” says Osborn-Senatus. “If someone wants to be involved, just let us know. Donations of money, food or your time — that’s a year-round need. And if you are facing difficult decisions financially and have never been to a food pantry, come, that’s why we are here. We try to meet people where they are.”