What Is Scaffolding in Education? An Overview for Teachers

We frequently urge teachers to scaffold learning to support students. But what is scaffolding in education? Does it really work? How can teachers use it in their own classrooms? Here’s what you need to know.

What is scaffolding in education?

Imagine a construction crew building a skyscraper. They use scaffolding to help support the structure as it gets higher and higher. As the building becomes strong enough to stand on its own, they slowly remove the scaffolding until the project is complete.

Scaffolding in education works very much the same way. It provides a system of support for students to build their skills, first through demonstration and modeling, then through guided practice. Over time, students gain confidence and are able to complete tasks or recall knowledge independently.

Instructional scaffolding also breaks larger concepts and skills into smaller, more manageable chunks. Just as a construction crew builds a skyscraper floor by floor, teachers build knowledge and skills in their students a bit at a time.

History of Instructional Scaffolding

In the 1930s, Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky developed a concept called the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Essentially, he noted that it was important to test students both on their ability to complete tasks independently and on which tasks they could do well as long as they had some assistance. A person’s ZPD includes tasks they can do with support but aren’t quite ready to tackle independently. Learn much more about the Zone of Proximal Development here.

In 1976, researchers David Wood, Gail Ross, and Jerome Bruner revived Vygotsky’s work and applied it in their report “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” They found that encouraging students to challenge themselves in grasping new concepts within their ZPD leads to success in learning. They called the process instructional scaffolding, and it soon became a popular standard in classrooms everywhere.

Why is scaffolding in education important?

Think back to when you first learned to ride a bike. No one climbs on and gets it right immediately. In fact, most people don’t even start on an actual bicycle. Instead, we usually give toddlers a tricycle, which helps them learn the concepts of steering and pedaling without having to worry about balance.

When kids get a little older, we offer them a bike with training wheels. Now they’re higher off the ground, and things are a little less stable. Still, they’ve got plenty of support to stay upright as they build their confidence. Often we ride alongside them on our own bikes, showing them the proper safety procedures and modeling responsible bike behavior.

When it’s time to take the training wheels off, we still don’t expect them to balance and ride off right away. Instead, we hold on and run beside them, helping them get the feel of it. With practice and time, most kids eventually learn to ride off on their own. They no longer need the scaffolding support of training wheels or an adult to steady them. They’ve mastered a complex skill, piece by piece.

Consider what might happen if we simply gave an 8-year-old kid a bike and told them, “Good luck!” While some kids might battle their way to success, the vast majority of them would likely just give up after the first few painful falls. Scaffolding in education helps kids gain the confidence they need, even when the task seems nearly impossible at first.

What does instructional scaffolding look like in the classroom?

Scaffolding is a type of explicit instruction. Teachers provide key information up front, then model the expected behavior for students. The instructor provides tools and guidance to help students as they begin to practice, individually and with their peers. Throughout the process, the teacher regularly checks for understanding and gently corrects mistakes. Eventually, students are able to complete the behavior independently.

Let’s take a look at this concept in a little more detail, using the example of a lesson about adding single-digit numbers (addition facts).

Break Information Into Chunks

During the planning process, an instructor looks at the overall learning objective. In this case, it’s teaching kids their addition facts for numbers 1 through 9. That’s a big skill, so the teacher breaks it down into chunks. They begin by teaching students what happens when you add 1 to any number.

Provide Information

At the beginning of the lesson, the teacher activates any background knowledge students already have. In this case, they remind students what the word “add” means, as well as what the plus symbol looks like and signifies. They also ask the class to count out loud together from 1 to 10.

Next, the teacher explains the new concept they’re learning today, pointing out that when you add 1 to any number, the answer is always the next number in sequence. They write an addition equation on the board: “3 + 1 = 4.”

Model/Demonstrate

Now the teacher explains the concept in several different ways, using a variety of tools to support the process. They display a number line and put their finger on the number 3. Then, they demonstrate that adding 1 moves their finger to the number 4.

The teacher also holds three markers in one hand and one marker in the other. She counts the total out loud: “One, two, three … four.” Finally, they show a hundreds chart, place a marker on the number 3, then move it one space along to number 4.

Guided Practice

Now students are ready to begin trying this concept with assistance and tools (scaffolding support). The teacher begins by returning to the number line and placing their finger on the number 8. They ask students what they should do to add 1, and the students tell them to move their finger one space to the right. “What’s the total?” asks the teacher? “Nine!” says the class. The teacher writes the equation they’ve just formed on the board.

The teacher passes out hundreds charts to all the students and writes the equation “5 + 1” on the board. The students place their finger on the number 5 on the chart, move it to 6, and help the teacher finish the equation. They continue to practice together using different tools like the number line, math manipulatives, and the hundreds chart.

Supported Practice and Correction

Next, the teacher writes five equations on the board and asks students to write them down on a piece of paper. Using the tools they have, like number lines and manipulatives, the students work to solve the equations on their own, writing down their answers. The teacher circulates, providing immediate feedback to anyone who’s struggling. This ensures they’re learning the process correctly and not forming any bad habits.

Gradual Release

Now, the teacher asks students to put away all the tools except their manipulatives and solve a few more problems on their own. Afterwards, students work in pairs to see if they have the same answers. If not, they talk about it and work together to decide on the correct response, with help and guidance from the teacher as needed.

Independent Practice

Finally, the teacher gives students five more equations to practice, this time without using any tools. In effect, the instructor is removing the scaffolding, encouraging students to try the skill on their own without outside assistance. At this point, some students will likely succeed while others still struggle. The teacher checks for understanding and determines who needs a little more help.

This is just one simple example of scaffolding in education. There are many more ways to scaffold learning, including peer instruction, group work, and tools like anchor charts and graphic organizers. Find more details on scaffolding in education examples and strategies here.

Does instructional scaffolding really work?

There’s no doubt that this is an effective education strategy, and it’s already widely used in subjects like reading, math, and science. It’s especially popular in elementary-level classrooms, where students are building foundational skills and behaviors step-by-step.

But scaffolding has applications in every subject, at every age. Teachers can use it to help students gain a deeper comprehension of material, modeling behaviors like critical thinking and analysis. They can take complex issues, like the causes of World War II, and break them into smaller topics, working through each to ensure their students really understand them. This is a valuable technique for every teacher to learn, practice, and use regularly.

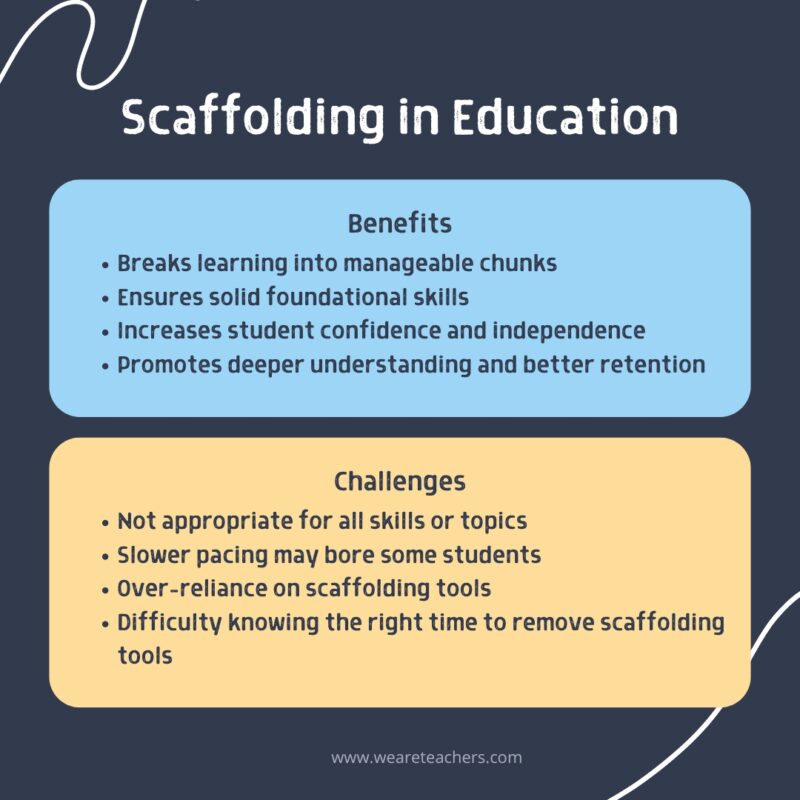

Benefits of Scaffolding

Those who use instructional scaffolding say it:

- Breaks learning into manageable parts so students don’t feel overwhelmed

- Ensures foundational skills are solid before building on them further

- Provides supports so students feel more confident trying new things

- Encourages independence by gradually removing supports as they’re no longer needed

- Promotes deeper understanding and better retention of material

- Invites class participation from all students by providing tools to support thinking and sharing

- Reduces student frustration by slowing the pace and supplying support tools

- Provides more formative assessment opportunities for educators

Challenges of Scaffolding

There are times when scaffolding doesn’t work well, making it just one important instructional strategy among many. Here are some potential issues:

- Students may become overly reliant on scaffolding tools if the instructor does not remove them gradually and appropriately.

- Some students may be bored with the slower pacing of scaffolding and ready to move on before their peers.

- It takes skill and practice to learn to recognize when students are ready for scaffolding to be removed so they can work independently.

- Removing scaffolding too soon can break down the confidence students have built over time.

- Scaffolding isn’t ideal for teaching skills like problem-solving and creativity.

- Some worry that scaffolding risks lowered expectations of student achievement.

When scaffolding isn’t the right strategy, teachers can try other methods like project-based learning, play-based learning, or inquiry-based learning.

Scaffolding vs. Differentiation

Sometimes teachers confuse scaffolding with differentiation. But the two are actually pretty different.

Differentiated instruction is an approach that helps educators tailor teaching so that all students, regardless of their ability, can learn the classroom material. In other words, tailoring teaching to meet the needs of different learning styles.

Scaffolding is defined as breaking learning into bite-size chunks so students can more easily tackle complex material. It builds on old ideas and connects them to new ones.

For more on scaffolding, check out Ways To Scaffold Learning.

For more articles like this, be sure to sign up for our newsletters to find out when they’re posted!

Source link