Madison author Heather Swan’s ‘Where the Grass Still Sings’ embraces both art and science – Isthmus

Madison poet and essayist Heather Swan doesn’t kill insects she finds in her house — she’ll take a bug outside. She doesn’t swat flies.

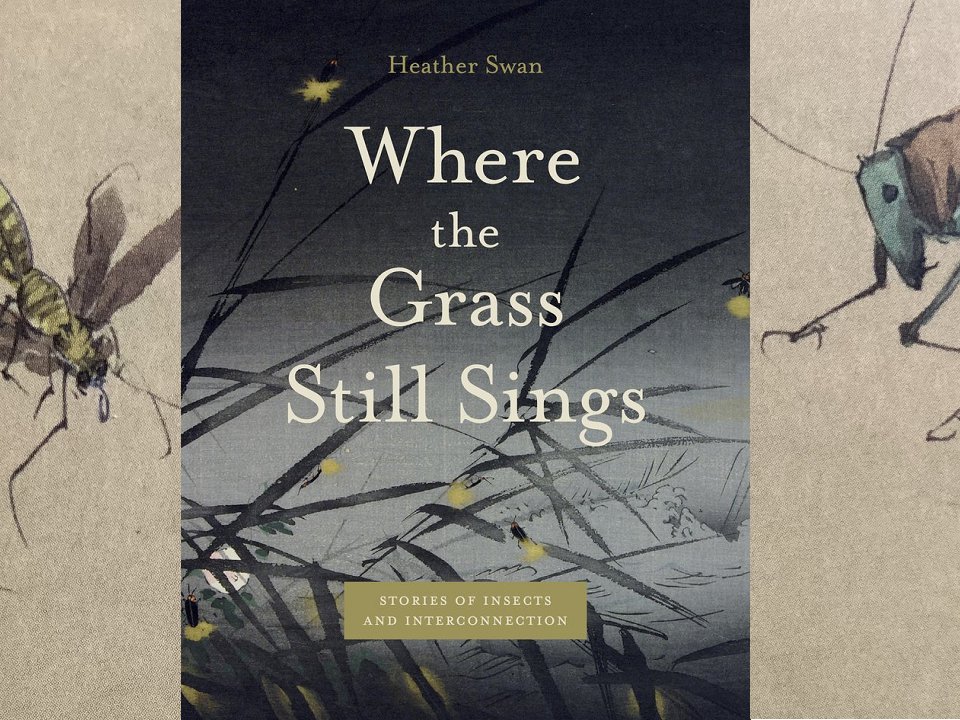

“Most people don’t care about insects, or they don’t like them,” says Swan. But she finds them beautiful. “All creatures are valuable,” says Swan, and that’s a fitting motto for her latest book, Where the Grass Still Sings: Stories of Insects and Interconnection (Penn State University Press). “It’s not a typical book,” Swan says, terming it “eclectic, a mosaic of projects and insects and ecosystems.”

Swan will be appearing at the Wisconsin Book Festival’s fall celebration weekend twice on Oct. 19, with Barrett Klein discussing his book The Insect Epiphany (1:30 p.m.) and with Madison poet Catherine Jagoe in a session called Writing the More-Than-Human World: A Reading and Conversation with Heather Swan and Catherine Jagoe. (3 p.m., both sessions in the Wisconsin Historical Society auditorium).

Where the Grass Still Sings is a compelling hybrid of personal essay and environmental reportage, with additional reporting on the arts. Each chapter engages with an environmental issue specifically having to do with insects, and each is followed by a “gallery,” an illustrated report on an artist whose work is primarily based on insects. It’s a fertile area for Swan, who has previously written Where the Honeybees Thrive: Stories from the Field and two collections of poetry, A Kinship with Ash and Dandelion. She sees Where the Grass Still Sings as a companion piece to Where the Honeybees Thrive.

The new book is physically designed almost like a field notebook. With heavy cream pages, it’s very touchable. A generous number of colored art reproductions are included, something that was important to Swan. Penn State University Press “understood that I wanted full color images and that I wanted it to feel like the book itself was a work of art,” says Swan. “Other presses were hesitant to do that.”

Chapters tell of Swan’s encounters with persons worldwide who are working to save insects, from María Luisa Hincapié restoring native orchids and their pollinators in Colombia to Wisconsin cranberry grower Corey Searles, who is restoring native plants on his land.

“Insects are obviously in decline,” says Swan. “We don’t realize how fundamental, how crucial they are, because they are small.” And it’s not just pollinators that are threatened. “Beetles regenerate soil, [but] we spray them, we swat them. Insects are food for so many creatures including birds.”

Swan found the artists she spotlights “celebrating the beauty and strangeness of insects”

over the years, in galleries or through articles in papers or magazines, and wrote to them: “I built relationships with all of the artists and found a great community to think and work with.” Artists include the instructional environmental comics of Liz Anna Kozik, the insect quilts of Susan Carlson, and the intricate pen and ink drawings of Rosalind Monks.

This cross-disciplinary approach appeals to her. “I come from a university setting,” says Swan, who is a senior lecturer in the UW-Madison’s English department. In academia “it is not always easy for disciplines to work together,” but she feels that because there’s “no one solution” to environmental problems, a “multifaceted approach” makes sense.

She calls artists “our most visible profession that uses creativity,” but notes that creativity enters into the work of scientists as well as farmers — for example “they have to be creative in how they are going to take the toxins out of the soil.” While artists may be top of mind when we say creativity, “there is creativity in all these fields.”

Hope is a throughline in the book. While there are many reasons to be despondent, the book focuses on ways to come up with solutions instead of throwing in the towel.

“Especially with young people right now, growing up with so much bad news, I wanted to show them there are so many ways that good is happening and so many people doing creative and brave things,” Swan says. “I wanted to find strategies for hope.” She points to a chapter on Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie. “Here is a space that was once an arsenal and now it is a tallgrass prairie. We can make change.”