Can Monona help solve Madison’s housing crisis? – Isthmus

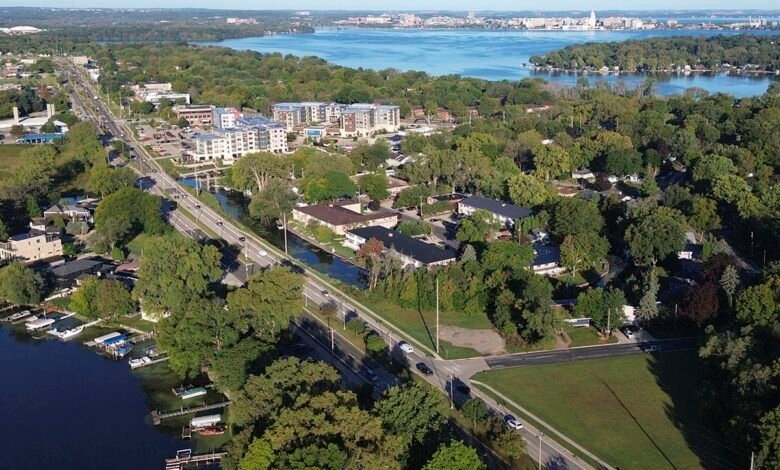

Monona, a city surrounded by a city famously surrounded by reality, might prove to be the real deal in the quest to house the influx of new residents Madison’s booming economy is expected to attract in the next several decades.

Wait, what? Housing — in “landlocked” Monona?

Hemmed in by Lake Monona and the city of Madison, Monona lacks the cornfields along its borders that are easy pickings for other communities to annex, subdivide and develop. Madison, Sun Prairie, Middleton and Fitchburg are where 85% of the 16,000 new rental housing units in Dane County were built from 2010 to 2021, according to the April 2024 Dane County Regional Housing Strategy report. Monona accounted for a scant 2%.

But while Monona may be landlocked (and lakelocked), it isn’t airlocked. And now, some city leaders are looking upward for how one small suburb can do its part — and, maybe, much more — to help address the Madison area’s housing needs.

A prominent Madison-based urban planning consultant believes Monona’s time has come.

“I think there is significant potential,” says Vandewalle & Associates principal planner Rob Gottschalk, who has been instrumental in the redevelopment of Madison’s Capitol East corridor into a vibrant residential, recreational, commercial and cultural core. “If [Monona] wants to really optimize that potential for its future, there’s great opportunity there.”

Why Monona, and why now?

Taller buildings and greater density, which have sometimes been met with neighborhood and political pushback in recent years, are getting a more favorable reception these days. Also, the area’s housing crisis is converging with a budget squeeze for Monona. Wisconsin caps property tax increases at the percentage by which new construction has increased property values. This handcuffs the Mononas of the world, where a Qdoba here and a Chipotle there are not enough to move the needle. There’s been so little recent building activity that the city is limited to a negligible levy increase for 2025.

A November referendum will ask voters to permanently increase the annual limit by $3 million. But even if it’s approved — no slam dunk, considering that it would raise the city portion of Monona property tax bills by 30% — the referendum is regarded as only a partial fix.

Feeding into the Madison area’s hunger for housing could give Monona more budget breathing room while also addressing an urgent regional priority.

“If we’re going to increase the population, increase our tax base and become sustainable at some point with our finances, we really have no choice but to grow,” says Monona Ald. Patrick DePula.

A Version of East Wash

“Growth” is an unfamiliar term in the civic discourse of a small city that’s been getting smaller. While Dane County’s population has doubled over the past half-century, Monona has been the outlier within. As high schoolers aged up, moved out, and made their parents empty nesters, Monona was the only city in the metro area to shrink — from its 1970 peak of 10,420 residents to 7,533 in 2010, according to census figures compiled by the Wisconsin Department of Administration. Even after rebounding to 8,624 in 2020, that’s a loss of 17% over five decades.

With no way to expand its borders and develop outward, Monona is actively exploring how “upfill” redevelopment could bolster its tax base and stabilize its municipal finances.

“Do I think there are opportunities for redevelopment or development in Monona? Absolutely,” says Olivia Parry, a senior planner with Dane County and project manager for the county’s recently completed Regional Housing Strategy report. The strategy identified a need for 139,000 new dwelling units between now and 2040 to accommodate population growth and replace aging housing stock.

On the southern edge of Monona, officials are eyeing the redevelopment potential of vacant, blighted, undersized or underutilized commercial properties along East and West Broadway — the four-lane, landscaped boulevard refashioned from the old South Beltline in the 1980s.

The two-mile span of Broadway from South Towne Mall to Stoughton Road includes potential housing sites that are closer to job centers like downtown Madison, the UW campus, American Family and Epic than many of the urban and suburban areas where new apartment development is flourishing.

“We’re sitting on a gold mine that we’re not utilizing,” says DePula, who co-chairs the Monona plan commission. Broadway “should be a smaller version of East Washington Avenue, with eight- to 10-story buildings up and down that corridor.”

As Scott Harrington, a principal planner with Vandewalle, points out, “Monona is closer to downtown Madison than most of Madison. It’s got incredible accessibility.”

With vehicle lanes, bike routes, sidewalks and, soon, bus service, Broadway is a veritable axis of access. But hardly anyone lives there. A few multifamily buildings and waterfront cottages face the street; otherwise, it is mainly commercial.

And yet, amenities that new residential developments often struggle to attract — including shopping, dining, health and recreational facilities — are already in place on and near Broadway for what could be a neighborhood with walkability scores through the roof…and swimming pools on the roof.

“Monona is almost perfectly placed,” says City Administrator Neil Stechschulte. “You work on the west side [of Madison], you work on the east side — you can get everywhere in our area from Monona.”

And not just by car. Beginning in early 2025, Monona will be served by full-scale public transit. The city has contracted with Madison Metro to replace its limited-service Monona Express shuttle. The new bus routes with expanded schedules could make parts of Monona even more viable for housing development.

“Owning a car is a very expensive thing,” says Parry. “If you live on a transit corridor, your housing expenses are going to be less — so it’s a great place for affordable housing. It’s a great place for workforce housing. It’s a great place for housing in general.”

A Broadway revival?

The beginnings of a potential Broadway revival are already in place: Yahara Terrace is a 121-unit mixed-use apartment building on the site of a former a mobile home park near the Beltline’s Monona Drive exit; and The Current, anchored by 145- and 96-unit apartment buildings, features local restaurants, a hotel, a public park and a marina at the junction of Broadway and Bridge Road.

Harrington, who worked on the complex riverfront plan that spawned The Current, says the success of that project and Yahara Terrace helped “prove the market” for high-density residential development in the Broadway corridor.

“People have underestimated what you can do in Monona before,” Harrington says, “and yet these projects keep showing that there’s more power in the market there than people give it credit for.”

Part of the area’s unique appeal is that multistory buildings could offer tenants on the upper floors sweeping views of postcard-worthy scenery. At heights and densities approaching East Wash proportions, a Broadway high-rise could afford breathtaking sunset vistas silhouetting the Capitol skyline.

Two other projects under construction on Broadway will not reach skyscraper dimensions, but have other notable attributes. Besa — a smaller-scale development across from The Current — includes owner-occupied live/work units as well as market-rate apartments. Farther east, the nearly completed Broadway Lofts & Townhomes offer affordable workforce-priced units.

During the COVID pandemic, Monona’s largest business — WPS Health Solutions — became a virtual employer and its sprawling corporate campus on West Broadway a ghost town. The insurer’s conversion to a remote workforce left nearby retailers reeling from the loss of their former customers.

Unlike many businesses, WPS did not order its employees back to the office when the pandemic subsided. Most of them continue to work remotely, allowing the insurer to consolidate its physical footprint in its main headquarters, and make its surplus buildings, land and parking lots available for redevelopment. One of the structures has become the new home of One City Schools.

“We’d love it if they were just going back to full strength, and get that economic benefit of all those employees in and out every day, but it doesn’t feel like that’s going to happen,” Stechschulte says. “They don’t necessarily need that physical space. Let’s do something cool with that.”

Word of the WPS site’s availability was soon followed by the news that Top Golf, a national chain of indoor/outdoor driving ranges, is planning a recreation and dining venue on the site of a small office park between WPS and South Towne. South Towne itself has recently filled long-vacant spaces with new retailers, but unused outlots and unneeded parking areas are being marketed for future development.

‘Highest and best’

Broadway and its intersecting thoroughfare Monona Drive — each approximately the same length as Madison’s Capitol East corridor — are dominated by low-density commercial buildings. Many contain popular and prosperous businesses and are in good repair; a few are even architecturally distinctive. Others show the effects of deferred maintenance and neglect.

DePula’s refurbished Salvatore’s Tomato Pies restaurant occupies part of an aging strip mall that he cites as an example of Monona Drive’s unrealized potential. “The highest and best use of this is to build five stories of housing above it, with commercial on the ground floor,” DePula says.

That vision is beginning to take hold within a few blocks of Sal’s. Several large market-rate housing projects on or near Monona Drive have been approved or proposed: The Bloom, a 98-unit mixed use development that recently broke ground on the former site of a bar, an antique store and a bank drive-thru; Monona Pines, 45 apartment units on a former fast-food and oil-change site; and a two-phase, 242-unit complex on Owen Road, where the shuttered Village Lanes bowling alley has stood empty for three years.

Stechschulte, who was Sun Prairie’s longtime economic development director before coming to Monona in 2023, says Madison’s Capitol East corridor provides a better model for Monona than the sprawling, auto-centric growth spurt Sun Prairie has experienced. Madison was able to reinvigorate those blighted blocks without annexing a single acre of land or paving a single cornfield.

“I am a fan of the things that have been happening on East Wash,” Stechschulte says. “The isthmus is like a hyper-Monona. They’re landlocked more than anybody, so they have to go up.”

But “East Wash” only happened as a result of a long, careful process of planning and coordination among stakeholders in the governmental, financial and development sectors. Guided by Vandewalle consultants who helped not only create a vision but carry it through to implementation, they looked at the corridor as a whole and made intentional decisions about what should be built where.

“Corridor planning is a very significant tool that municipalities can use to green-light the types of projects that they want to see,” says Dane County’s Parry. “It takes a whole piece of existing infrastructure and says, how can we fulfill the priorities of our community within this given space? It allows you to identify areas where you want housing. It also signals to developers that you know this is what you want and where you want it.”

Gottschalk cautions that, in the absence of a cohesive plan, a spate of new interest in Monona after years of slow development activity might tempt the city to embrace every project of any type that comes its way — in the misguided belief that somehow, “one-by-one, they will add up to something great.”

‘Is there a vision?’

The Top Golf project illustrates his point. It may be, as city officials hope, a catalyst for compatible spin-off projects — much as the Capitol East district feeds off the sports and entertainment activity at Breese Stevens Field.

“There’s no other place in Dane County where we could look at a parcel that’s underutilized like South Towne and the whole commercial area that’s adjacent…to create a destination for Dane County and really make something spectacular there,” says DePula.

But “there’s a lot of detail and finesse that goes into that,” Gottschalk says. “It isn’t going to happen by accident. If each property owner is working in their own self-interest and you’re not thinking holistically about what environment you are creating, then you could get kind of a hodgepodge.”

Harrington, whose involvement with The Current convinced him of Monona’s potential, advocates planning for the entire Broadway corridor rather than sitting back and watching it develop piecemeal.

“Is there a vision, rather than just WPS putting a sign in the yard for the rest of the property, of the city being proactive and figuring out what would be the right thing there — not just from an economic standpoint, but from a community standpoint?” Harrington says.

“A lot of communities sell themselves short and are willing to take the first thing that comes along,” he adds. “There were some initial proposals in Cap East that were dramatically less intensive than what you see there today, and by some pretty well respected developers. And the city [of Madison] had the foresight and the courage to say no, that that isn’t good enough. But it’s hard to turn people away, especially when you’re first trying to prove the market.”

Development in Monona is currently guided by its 2016 Comprehensive Plan, which sets forth general goals and land-use preferences and is scheduled to be updated in 2026. And the city is maximizing the use of incentives like tax incremental finance (TIF) districts to make redevelopment projects that meet city goals financially viable.

“The prudent use of TIF to spur redevelopment,” said Mayor Mary O’Connor earlier this year in a report by the Monona Community Development Authority, “is the city’s #1 tool to encourage commercial and residential growth through redevelopment that will be necessary to increase the city’s tax base, provide more housing and amenities to its residents and reverse the trend of declining population.”

Monona this year created several “anticipatory” tax incremental finance districts, identifying the kind of development it encourages in blighted areas where no specific project is yet planned. One such district encompasses the East Side Club — a lakefront event venue near Olbrich Park that is not on the market, but which city planners have pegged as a future location for housing.

“The value of the site, located on the shores of Lake Monona with a very nice view of the isthmus, state Capitol and downtown Madison, has risen significantly to the point where the use and density…is no longer consistent with the value,” says a city planning document.

Not in what backyard?

Is there the political will for a city that has stayed small for decades to suddenly go big on housing? It is notoriously hard to please everybody — and sometimes, anybody — on development issues. Some folks don’t want affordable housing; some don’t want unaffordable housing. Some don’t want either, as long as they have what’s theirs.

Local real estate agent and developer Bert Slinde planned to replace the shuttered Village Lanes bowling alley, a strip mall, and the crumbling parking lot they shared just off Monona Drive along Owen Road with an apartment building that would include affordable “workforce housing” units.

Concerns about density and traffic prompted the city to limit the development’s size when it was approved in 2022. But the project languished as construction costs and interest rates rose, and Slinde shelved it.

This year, he returned with a proposal bigger, taller and denser than the one some neighbors had already felt was too big, too tall and too dense. And yet — nodding to economic conditions, Monona’s geographic and fiscal constraints, and the realization that the comings and goings of apartment dwellers would likely cause less ruckus than a bowling alley at bar time — the city approved the larger project with little dissent.

Slinde, like other developers of recent Monona projects, declined to comment for this story. But at a recent plan commission meeting, he drew parallels with the Monroe Commons condominiums he developed in 2006 on Madison’s near west side.

“When we built Monroe Commons, my gosh — people were losing their minds. ‘We want Ken Kopp’s [grocery store] to stay,’ and they’re the same people that go to Trader Joe’s now and have bought condominiums in the facility. So, change is difficult — I get it,” Slinde told Monona’s plan commission.

“Even those that originally were objecting…those are ironic situations, that they may very well be some of the same people that will live there,” Slinde said of his Monona project.

There tend to be fewer NIMBYs where there are fewer backyards. Recently, a developer who had experienced neighborhood pushback in a nearby community received a warmer reception in a less populous part of Monona.

When Northpointe Development proposed senior apartments across the street from a cluster of existing duplex-style condominiums in McFarland, the condo owners circulated petitions protesting that the project would increase traffic, hurt property values, and create too many “affordable” units.

But when Northpointe came to Monona with its plan for workforce apartments on East Broadway, there was little to no neighborhood opposition — partly because there is little to no neighborhood. In fact, homeowners in the city’s more established residential areas have cited sparsely populated Broadway as a more logical place for new multifamily housing than Monona Drive, where several such projects are already underway or proposed.

‘Let’s build up’

An indication of how willing Monona is to embrace higher density housing development may be that the three winning candidates in the spring 2024 city council election — DePula and fellow incumbents Teresa Radermacher and Brian Holmquist — were outspoken supporters of the idea.

“Let’s build up, with tall buildings in designated corridors,” Radermacher told the League of Women Voters in a candidate questionnaire. Holmquist, during a televised forum, advocated a level of housing density “that is unheard of in our community, and I think that is the direction that we’re going to need to move in.” Meanwhile, the candidate who most brazenly equated housing density with crime — a claim that DePula calls “a racist trope” — finished 5th in the field of six.

“There’s always a subset of people that have been here for a long time who feel that change is scary and don’t want to change ‘the character of Monona,’” DePula says. “But the reality is, we can’t survive if we’re not growing.”

Bill Graf is a freelance writer and editor based in Monona. He serves on the oversight committee for the community radio station WVMO-FM (98.7), where his commentary “The Lake Loop” is broadcast weekly.