Who owes the city of Madison nearly $13 million? – Isthmus

In 2023, Madison provided an estimated $20.8 million in police and fire services to the 658 state facilities located within Wisconsin’s capital city. In return, the state paid $8 million.

It’s a point of frustration for Madison officials, who say more equitable payments from the municipal services payments program would help the city’s long-standing structural funding issues: “They don’t need to pay 38% of their bill for services that Madison provided when they have $3 billion in surplus,” says Dylan Brogan, Madison city communications manager.

State-owned facilities are generally exempt from paying property taxes to their host city. But Wisconsin’s municipal services payments program, administered by the Department of Administration, reimburses cities for police, fire and waste removal services provided to local state facilities. The DOA calculates the amount owed from annual financial reports submitted by municipalities and makes its recommendations annually by Nov. 15.

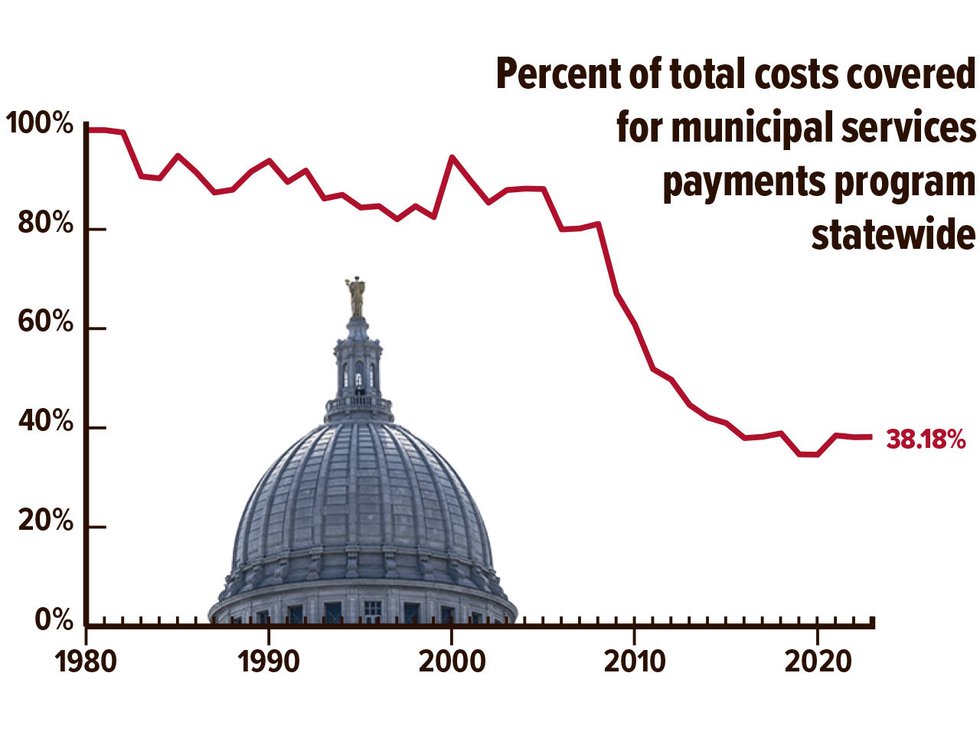

When the Legislature allocates less than what is recommended for municipal payments, funds are decreased by a uniform percent across all cities. The program’s 2023-25 budget appropriation was 61.8% short of what was needed, which is how Madison received just $8 million for $20.8 million in services.

For the last 10 years, the state has paid less than half of what it actually owes for municipal services statewide.

With Madison now facing a $22 million operating budget deficit, and a referendum vote in November to raise property taxes, city officials say it’s time for the Legislature to fully fund the municipal payments program and, as Brogan adds, “for the state to pay the bill it says it owes.”

City officials seem to have the ear of Madison’s Democratic lawmakers. Sen. Kelda Roys, a member of the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee, and Rep. Francesca Hong say increasing funding for the municipal services payment program and enacting broad local finance reform will be priorities for them when the Legislature reconvenes in January.

Roys says underfunding local government “absolutely has to get fixed in this budget.”

“If you’re only getting 38% of what you would be getting if a building were privately owned, you’re missing a huge chunk of your budget,” Roys says. “Those costs are being shifted onto all the other taxpayers in that municipality.”

Legislators created the program in 1973 with the intent, according to a March 2022 DOA memo, of decreasing residents’ property taxes by covering operating costs for municipalities’ services to state properties. But funding for the program has steadily declined in the decades since 1980, the last year it was fully funded.

For Madison officials, the irony is palpable.

“If they want property taxes to be lower, then they should share more shared revenue with the state, or they should pay this municipal service bill, or they should give local communities the option for a sales tax or Regional Transit Authority — all these things that make perfect sense for a community like Madison,” Brogan says.

Of Wisconsin’s municipalities, Madison receives by far the most funding through the program — 45%, according to a 2020 report by the nonpartisan Wisconsin Policy Forum — owing to its large number of state facilities.

According to DOA data from 2022, Madison has 658 state facilities eligible for the program, which total nearly $8 billion in value. Numerous state agencies have their headquarters in Madison, and UW-Madison also falls under the municipal service program’s jurisdiction.

The program’s payment goes into the city’s general fund and represents 1.9% of 2024 general fund revenues. Municipal services payments are the third-largest source of Madison’s intergovernmental revenues this year, representing 17.5% of the $45 million Madison brings in from state-level aid.

But since 2011, with the Legislature and Joint Finance Committee, which writes the annual state budget, under Republican control, the program’s appropriation has dropped from covering 51% to 38% of submitted costs.

Hong says that underfunding the program is a purposely divisive move by the Legislature’s Republican majority, and one that hurts Madison — the state’s fastest growing city — in particular. Despite Madison’s growth in population and outsized economic contributions to the state, “we’re seeing less of that come back to our services.”

“Do I think that’s deliberate by the majority party? Absolutely,” Hong adds.

A small group of Republicans, led by Waukesha Republican Rep. Scott Allen, did try in 2023 to fully fund the program with a budget motion, but the Joint Finance Committee never took up the measure.

Michael McKittrick, a legislative assistant for Allen, says that the committee’s focus was on finding common ground around an increase in shared revenue payments, so Allen’s motion “fell to the wayside.”

McKittrick adds that Allen has not committed to bringing the motion back in the upcoming budget, but that he “would not be surprised” if he did: “We’re definitely fighting for this one, because we want to make sure that our municipalities are being fairly reimbursed for the services that they’re providing for the state.”

Joint Finance Committee co-chairs Rep. Mark Born, R-Beaver Dam, and Sen. Howard Marklein, R-Spring Green, did not respond to requests for comment. Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, whose 2019 budget maintained a freeze on the program’s appropriation and whose 2021 and 2023 budgets advised $2 million and $1 million increases to the program’s funding, also did not respond to a request for comment.