Explainer: What is a budget referendum, and why is Madison considering one? – Isthmus

Why is the city of Madison considering a budget referendum?

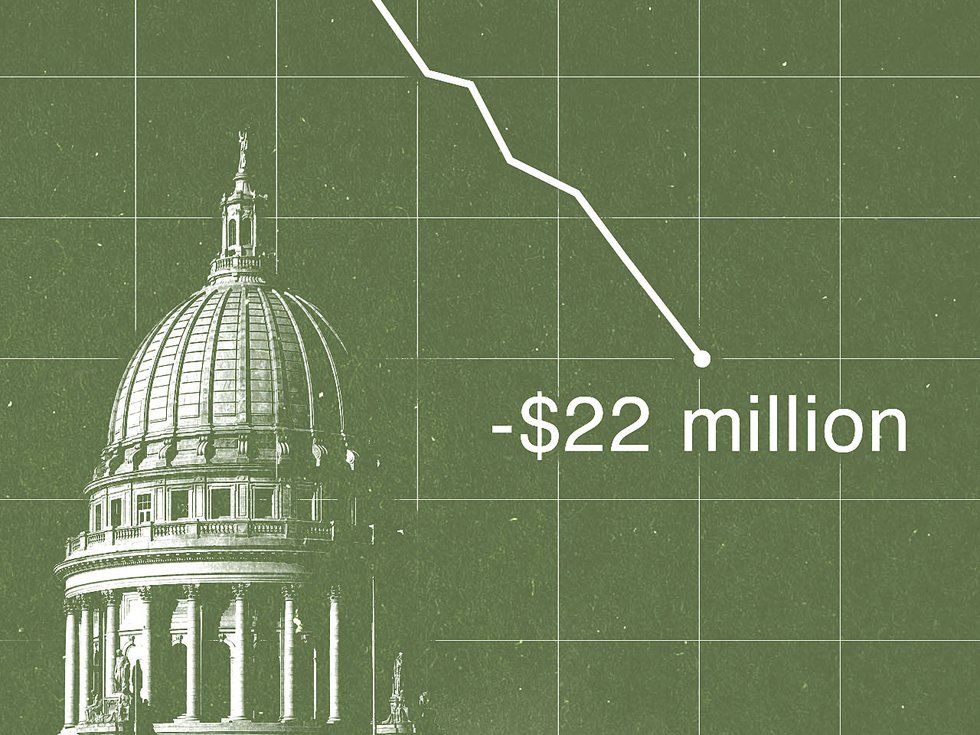

At latest count, the city faces a $22 million operating budget deficit. That leaves the city with essentially two options: impose steep cuts to staff and services, or ask voters to pay more in property taxes to close the budget gap.

What would the referendum ask?

Voters would be asked to approve allowing the city to exceed levy limits — the amount of money the state allows a municipality to collect through property taxes — in a specified period of time or on an ongoing basis.

The funding would go toward Madison’s operating budget, which funds day-to-day services. The money could not be used to support the city’s capital budget, which funds long-term infrastructure investments. Funds cannot be transferred between the two budgets.

Increasing levy limits would bolster revenue from property taxes, a crucial revenue source constituting 70% of Madison’s 2024 general fund revenues. The general fund is the city’s primary operating fund and makes up 40% of the city’s annual budget.

Has the city done this before?

Were Madison’s city council to approve a tax referendum, it would be the first time it has done so.

Referendums for municipalities are a “relatively new” phenomenon driven by tougher budget cycles, according to Jason Stein, research director of the Wisconsin Policy Forum. “As budgets have gradually gotten tighter, particularly as inflation has picked up, you’ve seen more school districts and local governments go to referendum,” he says.

Tax referendums are more well used among Wisconsin’s school districts, which have increasingly sought referendums in recent years. The Madison Metropolitan School District voted on June 24 to approve the inclusion of two referendum questions that will ask for $607 million in funding from taxpayers. The school district also went to referendum in 2020, with voters overwhelmingly approving $350 million in funding for capital and operating expenditures.

When does the city council need to make its decision?

City Finance Director David Schmiedicke told the city council during a June 24 finance committee meeting that he expects a referendum resolution to be introduced by July 16, possibly by “title only.” He tells Isthmus that the referendum language would be introduced by Aug. 6, at the latest.

However, the council is required to use data from the state Department of Revenue for certain metrics, which will be finalized on Aug. 15. The council would then have a 10-day period until Aug. 26 — the last day within the 70-day deadline for inclusion on November ballots — to approve a referendum question.

When would the referendum appear on the ballot?

If approved, Madison’s referendum question would be on the general election ballot on Nov. 5.

What would happen if the council decides against a referendum?

Were the city not to pass a referendum, it would have to find ways to reduce its budget gap. Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway has directed agencies to envision a minimum 5% spending cut, alongside ideas for increasing revenue. Saving $22 million would require cutting 220 positions.

And state law limits available revenue sources. Municipalities can institute service charges or fees, but the costs have to be directly related to the service provided, like an ambulance fee or parking fine. Failing to tie those costs would put the city in legal hot water: “If we are challenged in court, we have to prove the case — there is not a presumption that the city is correct in what it is doing,” Schmiedicke told the city council on June 18.

What are some of the fiscal reasons for a budget referendum?

Some critics of a potential referendum say that the city overspends on some services and projects, though city officials say that the city has fewer staff per capita than it did a decade ago and that citywide growth necessitates further investment in services and staff retention.

Inflationary increases in city employee wages and benefits and the loss of federal pandemic-era funding, in addition to the loss of revenue during the COVID-19 shutdown, have laid the path for much of the city’s current budget gap. The city’s projected 2025 expenditures sit at $431.4 million, with the greatest increase coming from an additional $14.5 million for salary and benefits increases; city revenues are projected at $409.4 million.

City officials also say that the state Legislature has left Madison behind while crafting budget policy. Under state law, cities cannot institute their own income or sales taxes, and Madison saw the lowest per-capita increase in municipality aid — $11 per resident — of any municipality in the 2024-25 state budget. Overall, Madison receives $29 per resident — the second-lowest amount in the state — compared to the statewide average of $142. That’s in part because the state’s revenue-sharing formula prioritizes municipalities with lower property values.

State aid constitutes 16% of Madison’s general fund revenues, and city officials say the revenue limits and lack of taxing authority put them in a bind. Ald. MGR Govindarajan tells Isthmus that the consideration of a referendum happened only “because the city has been underfunded by the state government for years.”

“The right thing to do, in my opinion, is go to referendum,” Govindarjan says. “Ask the voters to increase taxes a little bit and see if we can continue what we’re providing to the city.”

Neither Sen. Howard Marklein, R-Spring Green, nor Rep. Mark Born, R-Beaver Dam, co-chairs of the Legislature’s Joint Finance Committee, answered questions from Isthmus about whether there are plans to change levy limits or shared revenue formulas in response to municipalities increasingly going to referendums.